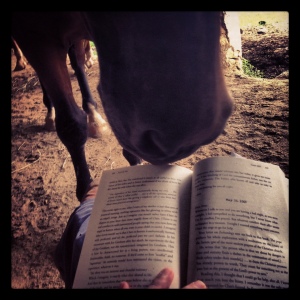

There are piles of work waiting for me, but I have spent the afternoon sitting quietly in a corner of the barn’s overhang, reading. The only sounds are the stomping of the horses’ feet, the occasional squonk of some nearby geese, and the whisk of wings as the barn swallows dive in and out of the barn. For awhile there was thunder, too, and I think I can still hear its echoes just over the hill.

Yesterday I provoked an argument with someone about whom I care a lot. In response to the simple question, “So, do you have any plans for tomorrow?” I lashed out, exclaiming that even though my summer might not look particularly busy, my time has been full, what with all my thinking and hiking and horse care and reading and efforts at routine and – heck, face it – feeling sorry for myself. I might not be working the same twelve hour days you do, I said, but trust me, I have been busy. Silence, an apology, and a touchy email later in response. I could learn something from the stoic silence of the horses as they swish tails at each other’s flies.

I have been re-reading Twyla Tharp’s book The Creative Habit. It has been just as hard to get through the book as the first time, but I promised myself I’d try it again after it came up in conversation more than ten times while I was away in Virginia. I have never enjoyed reading books that try to tell me what to do. Even when the advice has merit – like much of the advice in this book – its print form conflicts me about the process of reading itself. When I read, I’m undisciplined. I want to think, to muse, to visualize, to let my imagination wander. Commanding sentences interrupt that flow, and make me feel that I should be on my feet doing things instead of lost in a book.

Early in Tharp’s book, she talks about the sometimes surprising places in which we can form ritual. For her, each day’s creative routine begins with the early morning cab ride to her gym.

I begin each day of my life with a ritual: I wake up at 5:30 AM, put on my workout clothes, my leg warmers, my sweatshirts, and my hat. I walk outside my Manhattan home, hail a taxi, and tell the driver to take me to the Pumping Iron gym at 91st Street and First Avenue, where I work out for two hours. The ritual is not the stretching and weight training I put my body through each morning at the gym; the ritual is the cab. The moment I tell the driver where to go, I have completed the ritual.

When Twarp commands her driver, her day as a choreographer has begun – there is no longer any turning back or questioning. She commands me, “It’s vital to establish some rituals – automatic but decisive patterns of behavior – at the beginning of the creative process, when you are most in peril of turning back, chickening out, giving up, or going the wrong way.” I consider.

For nearly seven years now, I have begun each morning – seven days a week, except for some infrequent travel and a few weeks of summer job – by caring for horses. The number of horses has ranged from two to six, and the barns have ranged in proximity from a climb down a ladder from my bedroom to now, the farthest away, a fifteen minute drive. One of these horses, Nelson, has been with me for the full seven years. For three years now, after an unusual transaction that exchanged a security deposit for a one-eyed horse, I have owned him. Another, Wise Guy, owned by a woman who has become my good friend by proximity, has been with me for all but a few months. Yale, who rests in the barn as I write this, has been spending his retirement with me for about four years. He and I are both reeling from today’s veterinary care – him from the unexpected tubes and needles, me from the unexpected bill.

Is this my ritual? Tharp says that the ritual “erases the question of whether or not I like it.” Most mornings, this is not a question for me – I do like coming to the barn. There are a few moments of peace and quiet here before I begin whatever the day holds. The horses have simple needs – food, water, occasional medicine, a once-over check. They are predictable. Nelson walks to the right side of the overhang for his breakfast, Wise Guy waits in the center, and Yale stares blankly at me until I carry his trough to the left. If I listen to my alarm when it first nudges me awake, I have time to scratch Yale’s favorite spot, on his chest, and laugh as he stretches his nose to the sky in pleasure. Sometimes there is not much else about my day that is so even, and I silently thank the horses before I latch the door behind me. Sometimes this gratitude is expressed out loud. Sometimes it swirls into metaphors, though I seem to do better on this with some help. Sometimes it involves carrots.

But lately, during this impossible summer of questioning everything, I’ve also questioned my morning ritual. Later in the same chapter, Tharp also notes that we need to give up distractions when we’re trying to find a creative foothold. “It’s a simple equation,” she notes. “Subtracting your dependence on some of the things you take for granted increases your independence. It’s liberating, forcing you to rely on your own ability rather than your customary crutches.” Do I depend too much on the creatures who depend on me? Does being locked in to this ritual prevent me from seriously considering other options? When I am responsible each morning for two or six horses, I stumble out of bed, into my car, and to the barn. Conversely, when I am away from it, teaching or learning or administering or making, my routine starts before my alarm. I stretch, I pray, I read, I plan, and before breakfast I’m feeling more creative and energized than I do on the best of days here. But then again, there are a lot of other reasons for this alternate perspective on the world, and I’m not sure how much my barn ritual has to do any of it.

Arguments – mostly with myself, sometimes with others – have been like the distant thunder rolling in and out of this summer. Just today, in this quiet, slow time of watchfulness over a sick horse, I realized why my argument with this ritual may be getting so heated. Tharp’s ritual begins her creative life each day, her process of creating and mentoring dance. Over seven years of mornings, I haven’t yet figured out what process my own ritual is supposed to begin.