I want to teach Seth Godin how to throw a bowl.

I want to teach Seth Godin how to throw a bowl.

While he is fumbling through the centering process, I will quote Twyla Tharp:

“You’re only kidding yourself if you put creativity before craft. Craft is where our best efforts begin. You should never worry that rote exercises aimed at developing skills will suffocate creativity… An awareness of your particular set of skills will tell you what sets you apart.”

When the centering lump flies off the wheel for the first time, I will say,

“If thinking is bound up with action, then the task of getting an adequate grasp on the world, intellectually, depends on our doing stuff in it. And in fact this is the case: to really know shoelaces, you have to tie shoes.”

I will give an imaginary wet-clay high five to Matthew Crawford for this wisdom and humor. As Godin stands up to go to the pugmill with his clay, I will notice that his shoelaces are untied.

As he sits and tries to center again, his hands wobbling as his elbows are not yet locked into his body, I’ll quietly cite Carol Dweck, as quoted in Dan Pink’s book Drive:

“Effort is one of the things that gives meaning to life. Effort means you care about something, that something is important to you and you are willing to work for it. It would be an impoverished existence if you were not willing to value things and commit yourself to working toward them.”

I imagine that Godin is getting frustrated with his initial efforts. He might take a break, and walk over to the studio tables, where some advanced students are designing handles or carving surfaces. He might look at their work, and say, “Art doesn’t mean craft.” And I’d respond with Staley’s words, interrupting him before he could say more to my students – who are working hard, and shouldn’t have to listen to him.

“Art making is an essential part of the human condition. To make something special is fundamental to our humanity-from college freshman wanting to decorate their dorm rooms to wanting to dress up for a special occasion. This making things special is a form of caring.”

Godin counters me. “Art doesn’t mean painting, art doesn’t mean realistic and art doesn’t mean beautiful.”

I smile, and agree.

He says, “Art isn’t reserved for a few.” I keep nodding, more slowly this time, I look around our studio and sigh a bit.

Maybe he misunderstands my sigh for weakness, though, because he continues, “Art is something new, every time, and art might not work, precisely because it’s new…” and I interrupt him. Glaring, this time.

Now I use my own words.

Art is not magical thinking, and not ‘new,’ every time. Artmaking is a process. Even the type of art you like to write and blog about, Mr. Godin, the type of art that evokes change, must be based in deep knowledge and understanding of content, process, and person.

If you want to call it art, that is.

When you base a definition of being an artist as a desire to make change, you do my profession and the subject I teach a deep inservice. Art is so much more deep and expansive than this. Every politician says he wants to make change. As our government fumbles over and over again, I refuse to call any of its so-called leaders an artist. Change-makers are not artists, especially when their push for change is not rooted in deep understanding of process, craft, or people.

And by the way, when you base craft as the bottom of your perceived hierarchy, you misunderstand what it means to be a maker, of anything.

I know that you’re not talking about painting. You make that abundantly clear. But let’s say you’re talking about the art of another profession. Let’s say… well, I heard Sir Ken Robinson say recently: “Teaching is an art form.” I happen to agree with him, about a lot of things.

Teaching is not ‘new,’ every time. If I approached each day in my classroom with a new routine and new content, every day, my students would go crazy. Instead, the craft of teaching is rooted in deep knowledge of content, process, and person. (I realize I’m repeating myself. It’s deliberate.)

What REALLY happened in Klein’s photo. Content? Practice?

Every day that I teach, I make decisions based on what I have learned over the past decade, trying to adjust and develop my skills. Once I’ve learned to center – to create a classroom in which my students feel safe and comfortable taking risks – it’s time to dive in and open things up.

I have to be self-aware and lose myself in teaching at the same time. I have to create a climate that is organic, one in which my students can make their own art and their own change. None of this comes without practice and craft. Ten years in, and I’m just scratching the surface of what it means to do my art – my teaching. There are magical moments, sure, but no magical thinking.

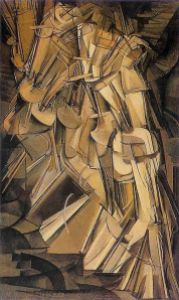

Duchamp studied and practiced making art – a lot of drawings and paintings, actually – for at least thirteen years before he came up with his Fountain. Yves Klein’s parents were painters, and he spent five years in art school before he began to make and exhibit. You posit their works as a redefinition of art. I counter that they had to learn the original definition, and learn it well, before they were ready to redefine it.

So, Mr. Godin, I think you should sit back down and practice centering for awhile. Right now, my students are in the midst of making hundreds of bowls that we will share with our community, fundraising for a organization that serves the homeless. We’re trying to use art for positive impact and change, in the world and in each maker who participates.

Maybe if you learn how to center, open the walls, and stretch your clay into a bowl, you can help us – since you like the idea of change so much? One of my students can help you, while I’m helping others. They are generous with their time.

But in order to get there, you’re not going to make anything new for a few days. Content, process, person. Find your rhythm.

Let me teach you how to use the pugmill. Welcome to Craft.