It’s a winter Saturday morning, and we just helped Chris Staley move a few stools and tables to set up the art center’s studios. My student Joe – who has perhaps taught me more than I’ve taught him – and I are about to spend the day learning from discussion and demonstration with Staley.

Joe is the youngest person of twenty or so in the room by at least twenty years. He is cradling an oval-shaped bowl Staley unpacked from a cardboard box – turning it over in his hands, analyzing how it might have been made. Before it is demonstrated, he will have already figured it out.

Staley tells us that the word ‘pedagogy’ means ‘child-led.’ Funny – with a grad degree in education and ten years in the classroom, I never knew that. He asks a group of strangers to share “the most important experience that has shaped your life so far.” After that, we are no longer strangers. He asks Joe his opinions about how learning and education work, and the whole room turns to listen intently as the teenager answers. He asks us how we might teach people to be better listeners. The room collectively pauses, takes a breath, listens intently. None of us are children – but while Staley is throwing and altering cups on the wheel, the focus of the day is clearly pedagogy.

“The quality of your education is based on the quality and sophistication of the questions you’re being asked,” Staley tells us. “It’s no longer OK for pottery teachers to just teach pottery. We have to teach why.” He continues to put cups and bowls on wareboards as he talks. He tells us that once he challenged himself to make forty cups in a day, but none of them could duplicate or reference any form he had ever made before. Joe and I both smile. We agree, in whispers, that we want to try this. And I wonder – why?

As a teacher, how often do I ask those ‘whys’ in the classroom? Or of myself? It often seems there is never time, but I’m beginning to think that is an excuse for not covering the ground that is most essential. How often do I get at the deeper motivations behind what I teach, what my students are learning, and why?

Chris Lehmann posed this challenge in his blog recently: “At the heart of teaching is the idea that we should be intentional about what happens in our classrooms. To do that requires understanding of how we got to that moment with our kids ourselves.” Being intentional as a teacher demands the ‘why’ question – of our students, and maybe more importantly, of ourselves.

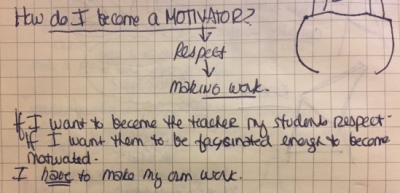

This workshop with Staley is not the first one I’ve taken. Several years ago, I spent a few intense days in a workshop with him at Peters Valley. I wrote half a battered notebook about this intensity, and one of my most essential questions wondered how Staley captured the full reverence and respect of a room of diverse students, almost immediately. I knew he had a tremendous reputation, but it was not only that. At the time, I credited it to that reputation, his work and his background. I was convinced that in order to become that teacher, I had to be making a lot more work.

Now I see things differently. I missed something that Staley did at both workshops, maybe because it is so natural and fluent in his approach. The teacher who has the highest respect of students is the one who is asking high-quality, sophisticated questions and building connections with and among students. That’s pedagogy – ‘child-led’ – which is its own craft. If you attach customary hierarchy to the terms, maybe it is better called an art. Yes, of course I need to make my own work – but this craft/art seems much more important to pedagogy.

So why were both Joe and I excited to try the forty cups exercise? I’ve been lucky to work with Joe throughout all four years of high school, in and outside of the classroom. We have asked each other a lot of questions, a lot of ‘whys’ – this is a natural part of our dialogue. Those questions have established trust and respect. The clumsy struggle of forty unique cups sounds like hard work – unless you know that curiosity, questions, and mutual respect are going to be part of every step of the process. Then it sounds like fun.

To practice really great pedagogy – and to inspire my students to create their best work – I need to establish a climate of great questions a lot sooner in my classes. After all, I see most of my students for only one semester, not four years. We cover so little content in a semester, especially in a school schedule that is inconsistent at best. The questions seem more important. How do I “teach why” sooner, faster, more nimbly?

It’s time to explore some methods to try this, and I hope to push myself to reflect on the experience here. And while sitting at the wheel, making cups.

We need much longer days for everything that goes into teaching craft.